Making atoms rotate through ultrafast quenching of magnetization

Excitation of a magnetic material with an ultrashort laser pulse is known to lead to an ultrafast loss of magnetization, yet a major question is how magnetization loss happens. Physicists in the CRC/TRR 227 show that the ultrafast loss of magnetic moment of atoms sets a rotation of the involved atoms in motion.

News from Dec 17, 2025

A century ago, Albert Einstein and Wander de Haas observed that a change in the magnetization of a metallic cylinder led to its mechanical rotational motion. This so-called Einstein-de Haas effect established in 1915 the fundamental physics understanding that magnetization carried by the materials’ electrons is a form of angular momentum, nowadays commonly called spin angular momentum. It remains however unknown how the Einstein-de Haas effect proceeds at ultrashort timescales of less than a picosecond (10−12 s) and at atomic length scales (10-10 m).

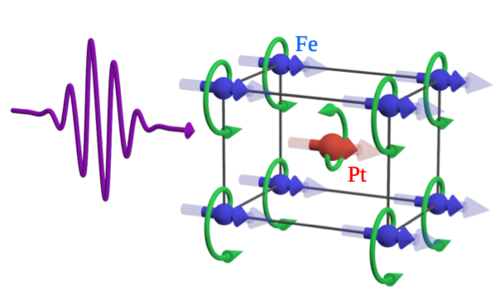

Physicists in the CRC/TRR, Markus Weißenhofer and Mercator fellow Peter Oppeneer, and M.S. Mrudul at Uppsala University, investigated this process through first-principles, time-dependent quantum mechanical calculations. They chose the ferromagnetic material iron-platinum (FePt) and used the time-dependent density-functional theory combined with the full dynamics of the Fe and Pt ions to investigate how FePt reacts when irradiated by a 20 femtosecond (20 x 10-15 s) laser pulse. Their calculations show that the laser pulse leads to an ultrafast loss of spin angular momentum of the electrons, which, importantly, sets into motion the rotation of the involved atoms around their initial positions, see figure. The generated rotational motion of the atoms is an unusual kind of lattice vibration that can be described as quanta of lattice vibrations – so-called phonons – that carry angular momentum, or chiral phonons. The physicists have further shown that the process that sets the atoms into rotational motion is mediated by the spin-orbit coupling of the electrons. It starts mainly after the laser pulse is over and reaches a maximal atomic displacement at about 80 fs after the laser pulse. The calculations thus provide an explanation of how angular momentum is first transferred to chiral atomic motions before these individual atomic motions on a much longer timescale convolve and lead to a macroscopic rotation of the whole material as is observed in the Einstein-de Haas effect.

Figure caption:

An ultrashort laser pulse (purple color) causes a reduction of the magnetic moments on iron (Fe, blue) and platinum (Pt, red) atoms in the ferromagnetic material FePt. This in turn generates a rotational motion of the individual atoms, or so-called phonons carrying angular momentum. Figure - courtesy of Markus Weißenhofer.

Article reference:

Generation of phonons with angular momentum during ultrafast demagnetization. M. S. Mrudul, Markus Weißenhofer, and Peter M. Oppeneer, Phys. Rev. B 112, L180407 (2025). Link: https://doi.org/10.1103/nt8w-47hb

Contact:

M.S. Mrudul, e-mail: mrudul.muraleedharan@physics.uu.se

Markus Weißenhofer, e-mail: markus.weissenhofer@physics.uu.se

Peter Oppeneer, e-mail: peter.oppeneer@physics.uu.se